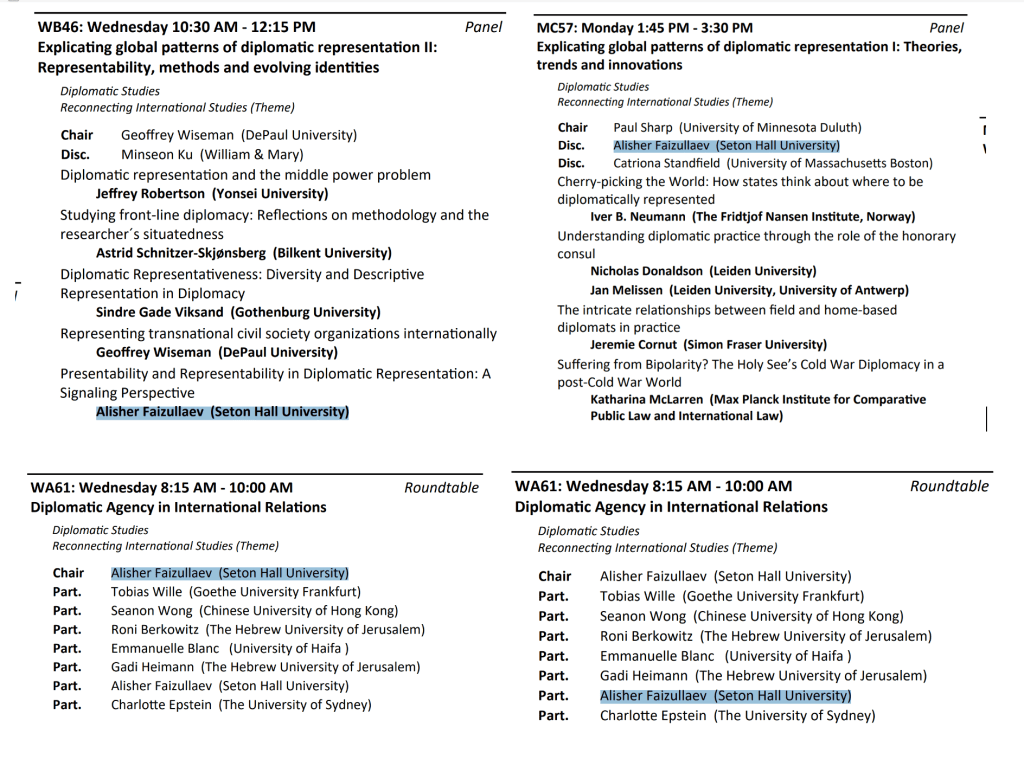

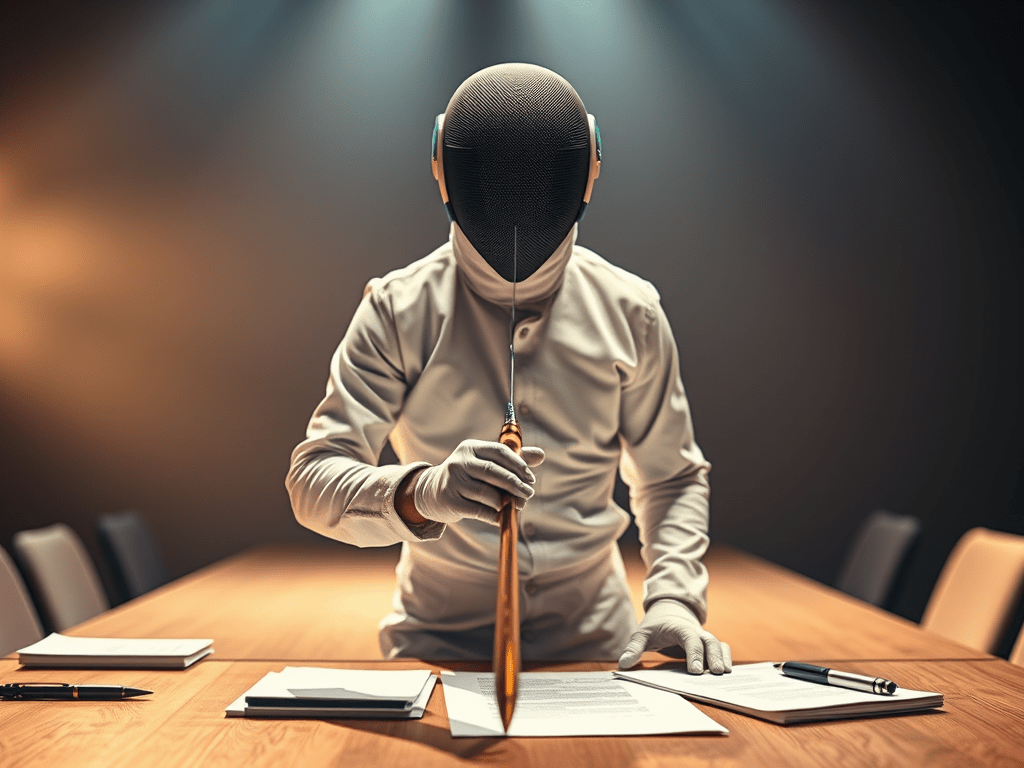

Fencing and negotiation may seem worlds apart – one takes place on a piste with blades, the other across a table with words. Yet both belong to the same ancient art: the art of strategic interaction.

As a former fencing athlete – Master of Sports and member of Uzbekistan’s junior team (foil) – and ex-ambassador, I have long felt how movement, timing, and awareness shape not only competition but also negotiation and diplomacy. In both fencing and negotiation, every move matters. You face an opponent who is, paradoxically, also your partner in creating the outcome. You win not by overpowering, but by reading, anticipating, and harmonizing with the rhythm of the encounter. And in diplomacy and negotiation, like in fencing, real emotions can be hidden behind the masks. I use negotiation for the universal craft and diplomacy for its grandest stage –statecraft – but the blade and the mask work the same in both.

In fencing the mask is literal – steel mesh that turns the face into a blank oval, forcing both combatants to read shoulders, hips, the tremor of a wrist. Yet it is never neutral: it magnifies micro-signals while shielding the eyes that might betray fear or triumph. The diplomat’s mask is subtler – posture, tone, the calibrated half-smile – yet it serves the same double purpose. It protects vulnerability and projects control. Skilled practitioners learn to inhabit the mask without letting it ossify. A fencer who freezes behind the grille is stabbed; a negotiator who mistakes his persona for his person concedes the agenda. The master, therefore, treats the mask as a mirror held at arm’s length: it reflects the opponent’s expectations back at them, distorted just enough to create openings. When to lower it – briefly, strategically – becomes the final feint. A flash of genuine frustration can lure an overconfident lunge; a flicker of empathy can coax the concession neither side thought possible. The mask, then, is less disguise than instrument: played well, it reveals more than it conceals.

Every fencer knows that victory depends less on strength and more on timing, distance, and clarity of intention. One has to read or assess the situation as a whole. The same is true for negotiators. The best negotiators, like skilled fencers, sense when to advance, when to pause, and when to let the other side make their move first. They know how to disguise intent without losing authenticity and how to stay calm amid uncertainty.

The art of anticipation lies at the heart of both disciplines. In fencing, you learn to read your opponent’s body before they move – a subtle shift in weight, a fraction of tension, the rhythm of breathing. You do not simply react; you position yourself where their next move will leave them vulnerable. You need to think several steps ahead.

In negotiation and diplomacy, the same principle applies. The skilled diplomat reads not just words but silences – the pauses that reveal doubt, the emphases that betray priority. Anticipation is not prediction; it is awareness so sharp that you move with events, not behind them. You create space for outcomes before others realize they are possible.

In game theory, Thomas Schelling described a “strategic move” as an action designed to shape another player’s expectations and choices. Both fencing and negotiation embody this principle. The expert fencer and the seasoned diplomat know that a move is never just a movement – it is a message. It signals, provokes, and reshapes the situation. The most decisive move often appears indirect: a feint, a pause, an invitation that makes the other commit first.

Both disciplines are simultaneous games – players act concurrently, ahead of, or in reaction to one another. This makes the game harder, yes, but infinitely richer in strategic possibility. In fencing, you cannot wait for your opponent to fully extend before responding – but you can invite the extension with a half-step back, a flicker of the blade. Negotiation follows the same logic: you don’t counter an offer you haven’t heard, but you can shape the silence – a pause, a raised eyebrow, a question left hanging – until the other side feels compelled to speak first.

In both games – whether with swords or with mental strategies – the mastery lies not in aggression but in presence, timing, and design. Each move expresses intention, communicates possibility, and defines the space of mutual understanding. However, the move can also be deceptive, and the best fencers and negotiators can distinguish the real one from the deceptive.

One might argue that many sports involve strategy, reading opponents, and tactical thinking. Yet fencing occupies a unique position. Unlike tennis, where the court separates and faces are visible, fencing occurs at conversational distance – close enough to read breath and tremor, masked enough to require interpretive skill. Unlike sports where reaction time eclipses strategic thought, fencing’s tempo allows for the pregnant pause, the deliberate invitation, the calibrated feint. And unlike games where implements mediate contact, the blade is direct extension of intention, a communicative instrument that signals as it threatens. Fencing, like diplomacy, emerged from the same crucible: the aristocratic culture of honor, where negotiations failed and swords spoke. They are not merely analogous – they are cousins.

Diplomats sometimes say that negotiations are “fencing with words.” Fencing, at its best, is a dialogue of minds expressed through movement. Both arts remind us that the finest victories are those achieved not only with strategy, precision, and timing, but also with grace. And perhaps this is the deepest parallel: in both fencing and negotiation, the bout ends but the relationship continues. The opponent you face today may be your partner tomorrow. The fencer who scores with brutal efficiency may win the point but lose the respect that shapes future matches. The diplomat who extracts maximum advantage may secure the agreement but poison the well for what comes next. True mastery, then, lies not merely in winning but in winning in a way that preserves the possibility of future engagement – fighting as if you might one day need to fight beside your opponent, negotiating as if today’s adversary might become tomorrow’s ally. This is why grace matters: it is not ornament but insurance, not weakness but wisdom. The mask comes off, the blades are lowered, and what remains is the memory of how you moved – and whether, when next you meet, the other side will trust you enough to engage again.

#fencing #foil #diplomacy #negotiation #strategy #move